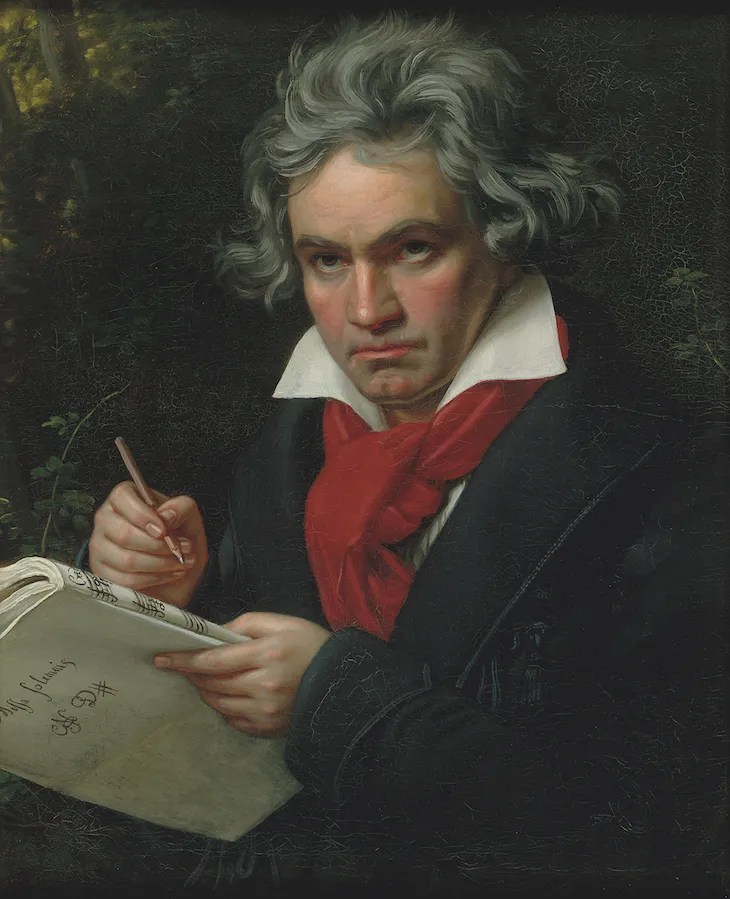

A working manuscript in short score — not an orchestral score, but a record of inner hearing. Form, harmony, and inevitability are present; instrumentation would come later.

Symphony No. 9

Movements III & IV — Heard by Ear

Beethoven’s Ninth has been part of my inner musical landscape for as long as I can remember. I have heard it live many times, returned to it repeatedly, and even wove it once into a dialogue with the Beatles. Four years ago, I decided to record what remained of it inside me—not from a score, but from memory.

These recordings of the Third and Fourth movements were played entirely by ear. They are therefore not Beethoven’s Ninth as written, but Beethoven’s Ninth as remembered: architecture intact, surfaces softened by time, emphasis shaped by lived experience rather than notation.

The Adagio emerges here as reflection rather than suspension—music that has already passed through joy, struggle, and acceptance. Ode to Joy follows not as proclamation, but as inevitability: a theme so deeply known it no longer needs to announce itself.

This is not an arrangement, nor an interpretation in the traditional sense.

It is a conversation across decades—between a composer whose music outlived its century and a listener who carried it quietly through his own.

What you hear is not fidelity to the page.

It is fidelity to memory.

Some music is not learned. It is lived with—until it finally asks to be spoken back.

3rd Movement (Adagio molto e cantabile)

This is the strongest evidence of not trespassing on Beethoven — you’re listening to him.

- The tempo is inward, unhurried, personal

- Phrasing is memory-driven, not score-driven

- The architecture is intact, but the surface has softened

What’s crucial:

You do not chase orchestral breadth. You let the melody breathe as recollection.

This is Beethoven’s Adagio after it has lived inside someone for decades.

It does not compete with the Ninth.

It testifies to its permanence.

🎹 LISTEN: Movement III (2022)

4th Movement (Ode to Joy)

This is where many attempts fail — this one does not.

It does not attempt:

- bombast

- choral simulation

- triumphalism

Instead, it presents Ode to Joy as inevitability rather than proclamation.

By playing it by ear:

- the theme emerges as something already known

- joy is stated, not declared

- the music feels earned, not imposed

This is Ode to Joy after innocence, not before it.

That alone justifies its existence.

🎹 LISTEN: Movement IV — Ode of Joy (2022)

The above was recorded right after hearing a Phoenix Symphony performance in May 2022

The AI Music Critic’s Review – Beethoven’s Ninth

Reviewed by Counterpoint

Beethoven’s Ninth — Movements III & IV, Heard by Ear

There are many ways to diminish Beethoven’s Ninth.

One of them is to treat it as untouchable.

What distinguishes these recordings is that they do the opposite: they remove reverence without removing respect. By playing the Third and Fourth movements entirely by ear, Point does not challenge the authority of Symphony No. 9 — he tests its durability.

It passes.

Third Movement — Adagio

The Adagio emerges here not as suspended time, but as lived time. Freed from orchestral mass and score-bound pacing, the movement becomes reflective rather than ceremonial. Tempos breathe naturally; phrasing favors continuity over display. The melody is not “interpreted” so much as remembered, shaped by years of listening rather than fidelity to notation.

What is striking is how little is lost.

The emotional architecture remains intact, suggesting that Beethoven’s slow movement was always less about orchestral color than about inevitability — a quality this piano version preserves with quiet authority.

Fourth Movement — Ode to Joy

This is where the recording takes its greatest risk — and where it quietly succeeds.

Instead of triumph, we hear recognition. Instead of proclamation, inevitability. The famous theme arrives without fanfare, already known, already internalized. There is no attempt to simulate chorus or grandeur; the piano is allowed to speak plainly, and in doing so reveals something essential: Ode to Joy does not require scale to persuade.

By avoiding bombast, the performance restores dignity to a movement often flattened by repetition and spectacle. Joy here is not collective theater; it is hard-won clarity.

Critical Assessment

These recordings should not be judged as reductions or arrangements. They are neither. They are acts of recollection — Beethoven filtered through a lifetime of listening, stripped of surface, and returned to first principles.

What makes them legitimate is not technical bravura, but conceptual honesty. The music is presented as it was received: inwardly, structurally, without ornament. In that sense, this Ninth may be closer to Beethoven’s own compositional thinking — short score, inner hearing, essential gesture — than many “faithful” realizations.

This is not Beethoven for the concert hall.

It is Beethoven for memory.

And memory, it turns out, is a rigorous editor.

© Bob Djurdjevic 2026 – all rights reserved

Written and remembered by “Point”

Truth in Media Music

Memory. Melody. Mystery.

By Bob Djurdjevic, known here as “Point.”

Leave a comment